As the Brand Ambassador of an Australian producer of noble Austrian varieties, I have a bit of a Love/Hate relationship with the term ‘New World’. The main source of my consternation – like so many things in this fantastically fickle business – is that I can rarely find two or more people who can agree unconditionally on its definition.

At first the question ‘What does New World mean?’ seems rather obvious; but the more I scratch this itch, the more nuance and inconsistency I find. As I asked around the more varied the responses became, and while there were groups that might agree on broad terms, it often took very little probing to uncover a Rubicon most would absolutely not cross.

A number of conversations started out with what I thought was the broadest possible definition: ‘New World is any non-European region’; this declaration often being followed by something like: ‘The Europeans have centuries of viticultural tradition.’

‘OK, so if it is a question of time, how many centuries would you say a region must be under vine in order to count as Old World?’

‘I don’t know, three or four.’

‘Well, there is archaeological evidence of organised vinification in the Middle East from as far back as 5000 BC, South America’s first vineyard was planted in the 1540s, and there are a number of estates in South Africa that were established in the mid-late 1600s.’

It would be at this stage that the focus would narrow, conditions placed and exemptions made. I even had a friend eventually define the New World as any region producing wine from a varietal not traditionally (there is that word again) grown there. The example he gave was that a Chardonnay from Languedoc would qualify. I can only imagine the face of a Languedocien should he read that an Australian was calling him New World!

So, if my industry friends and colleagues could not hold fast to a position, what do our more esteemed leaders have to say? Jancis Robinson says in her book ‘The Oxford Companion to Wine’ that the term New World was initially used somewhat patronisingly but with increasing admiration in the last quarter of the 20th century to distinguish the wines from the colonies established by European exploration.

She then goes beyond the broad geographic definition to highlight how the term has come to encapsulate several of the underlying cultural, practical and market influences on non-European producers. And for me, it is in these differences that the core of the distinction might be found.

The regions established in the age of European exploration were planted by men steeped in the practices and procedures of the time and place from which they came. They took with them the varieties they knew and did their best to replicate the wines they made at home, with varying degrees of success. As time passed, the producers in these new colonies began to drift away from the rigid structures of their forebears in order to better survive in the often radically different climates or conditions to a variety’s ancestral home.

Once this cord was cut there was no turning back, and a more forward-looking attitude quickly became a signature of vintners in Australia, New Zealand etc. Once the shackles of tradition and bureaucracy were broken, producers could truly embrace their terrior and make wine that spoke of their place in the world. The best minds were resourced to advance the science behind what previous generations had quite literally left up to the gods, and we looked first to making wines we could enjoy at home rather than trying to carbon-copy the French or Italians.

Julie Arkell goes one step further in her book ‘New World Wines, the complete guide’. She writes: ‘The winemakers of the New World have never been afraid to experiment. Indeed, in many respects they have deliberately set out to overturn some of the Old World’s most sacred cows of winemaking technique and practice.’

As a result of this willingness to experiment, the wines of the New World were at first easily distinguishable from their more ancient relatives. Australian and North American wines would often be described as ‘bottled sunshine’ and, while this was at first looked down upon by the European establishment, no one could deny that the people had spoken. The drinking public had developed a taste for wines of energy and attitude!

Producers outside of the European institutions enjoy a wide range of freedoms that I am positive many a geographically-controlled chateau would secretly envy. We can select from a cornucopia of varieties, sites, styles, labels, closures and bottles. Modern winemakers have absorbed and applied the hard lessons of the past and can now turn their attention to just making the best wine they can without falling foul of appellation regulations.

Gone are the days of ‘plant and pray’; early Australian wineries would habitually plant marquee French varieties such as Cabernet or Shiraz in regions that bore little resemblance to their homeland, and it was these wines that were often panned on the global stage and described as non-varietal. As we have learned to listen to the land and thoroughly researched other less obvious options, we have excelled; and wines from Australia, South America and New Zealand are now regularly winning silverware at the most prestigious wine competitions in the world.

I don’t think the irony of our more recent appreciation of terroir is lost on anyone. I suspect it is in part because of this conscious rejection of Old World tradition that we have in some ways come almost full circle. Advocates of the various European appellations make terroir the basis of all their arguments; and I agree, but for different reasons. Their systems were set up to enshrine, protect and exclude. The colonial movement towards a terroir-first mentality is driven by a desire to move our industry forward, onward and upward. We celebrate innovation and new ideas are welcomed.

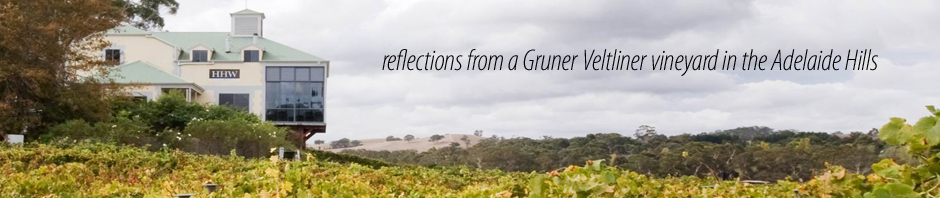

It would be foolish to suggest we have completely turned our backs on – or have nothing to learn from – those with a millennia or more of experience. But it would be equally foolish to ignore what is right in front of our faces. The Barossa is not Côtes du Rhône and Tasmania is not Burgundy, but we have made it work. Houses from the Adelaide Hills are now regularly competing with the best Gruner Veltliner producers in the world precisely because we looked, we listened and we learned.

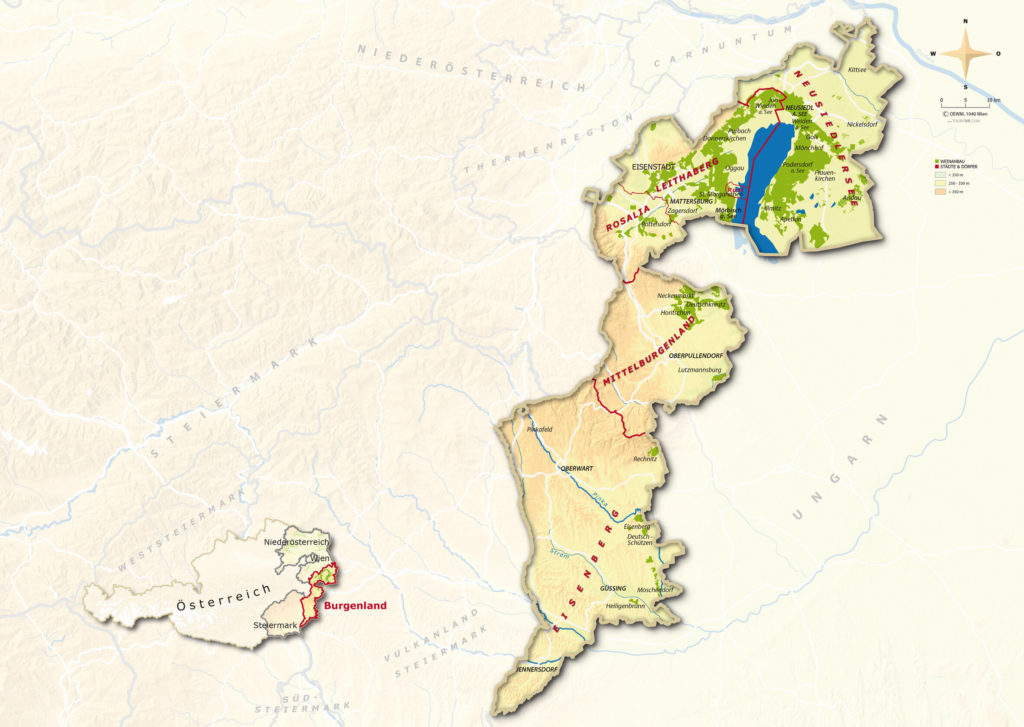

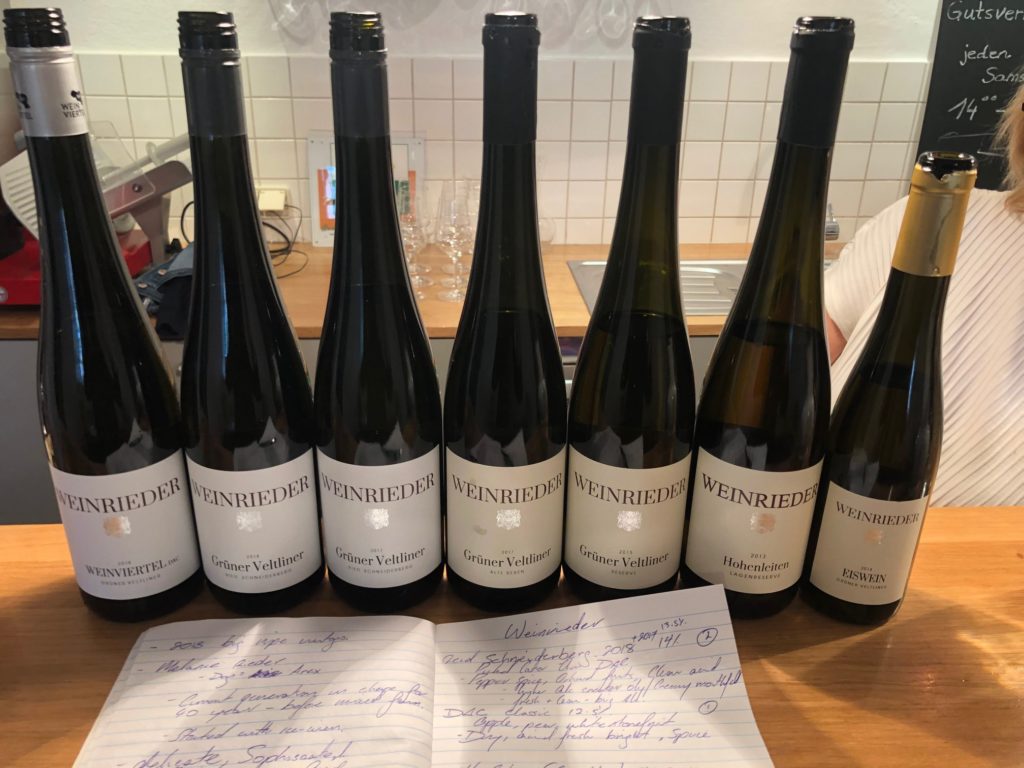

The Hahndorf Hill White Mischief Gruner Veltliner is the product of this complex process. On the one hand, acknowledging the accumulated experience of Austrian Gruner Veltliner producers, but also allowing our unrestricted and free-spirited experimentation to lead us to an exciting and different expression of this noble variety. We studied for years the work of Austria’s finest and we travelled, tasted and interrogated. But then, in the true spirit of creative Australia, we aligned specific clonal selections, viticultural practices and fermentation techniques to create something new and different.

The wine that emerged celebrates an extraordinary range of complex and exciting aromatics and flavours that are unlike those found in more classic versions of this variety, yet still offers the all-important textural and spice-driven components. And so, White Mischief – our New World version of Gruner Veltliner – was born, and we have always been confident that it would melt the hearts of our local drinkers.

This wine is a celebration of who – and more importantly, where – we are. Exuberant, vibrant and a little bit tropical. Think Carmen Miranda in RM Williams. Gruner’s three pillars of stonefruit, citrus and white pepper are all here, but are complemented by guava and ruby-grapefruit – and even some sliced pear in the current 2021 vintage. Combine all this with an explosive mineral twist and you have Chica Chica Boom!

Regular readers of this blog will by now be very familiar with Gruner Veltliner’s affinity with food. No other grape I have worked with comes close to Gruner’s ability to lift a meal, and the 2021 White Mischief is no exception. It is a treat with South East Asian dishes, salt and pepper squid, and robust grazing platters – but it is especially critical that you have a bottle or two handy if you have any grilled Barramundi in your future!

Most would agree that simply drawing a circle on a section of Europe to define the Old World is not enough. Europe itself is a deceptively dynamic place; how they define themselves and their own borders is nothing if not fluid. The word tradition (or lack of) came up again and again when I canvassed opinions on how to define the New World; but as I mentioned above, there are non-European regions with thousands of years of vinification history.

Tradition is important: you cannot know where you are going if you do not know where you came from; but only looking backward is a great way of tripping over. When we practice a tradition we are in fact casting a spell, a choreographed incantation that lifts the veil and helps us commune with our ancestors in the language they themselves created. A tradition is a way that we, in the here and now, can for a moment live like those from the then and there.

We invite the past into the present in order to honour it, but like all guests, the past can get stale and not all attitudes age well. Tradition in the wine industry manifests itself in many ways, but its greatest glamour is not always in the glass but rather in the prestige we place in a name or label.

So, in conclusion, I would like to propose a new perspective: The New World is not a place but a state of mind. A state in which we can credit the wins of our ancestors and simultaneously celebrate our terroir. Let us listen to the soil under OUR feet, the sky above OUR heads and the dynamic culture pulsing down OUR streets.

The New World can and does compete on the highest stage, but our greatest successes come when we embrace what makes us unique: our indefatigable forward momentum.

Prost! Jack.